Collaborating with and influencing others is the third skill set that the NeuroLeadership Institute has identified as being integral to effective and efficient leadership. Leaders must be able to collaborate with others as well as manage and influence others in order to make sure their businesses run smoothly. In a world of increasing interconnectedness and rapid change, there is a growing need to improve the way people work together.

Understanding the true drivers of human social behavior is thus becoming increasingly important. In an attempt to better understand these drives, social neuroscience explores the biological foundations of the way humans relate to each other and to themselves. They have found two emergent themes:

- Much of our social behavior is governed by an overarching principle of minimizing threat and maximizing reward (Gordon 2000).

- Several domains of social experience draw on these reward/threat brain networks for primary survival needs (Lieberman and Eisenberger 2008).

In other words, the brain treats social needs in much the same way as the need for food and water. The SCARF model, developed by David Rock with the NeuroLeadership Institute, summarizes these two themes within a framework that captures the common factors that can activate a reward or threat response in any social situation where people collaborate in groups (including all types of workplaces, educational environments, family settings, and general social events).

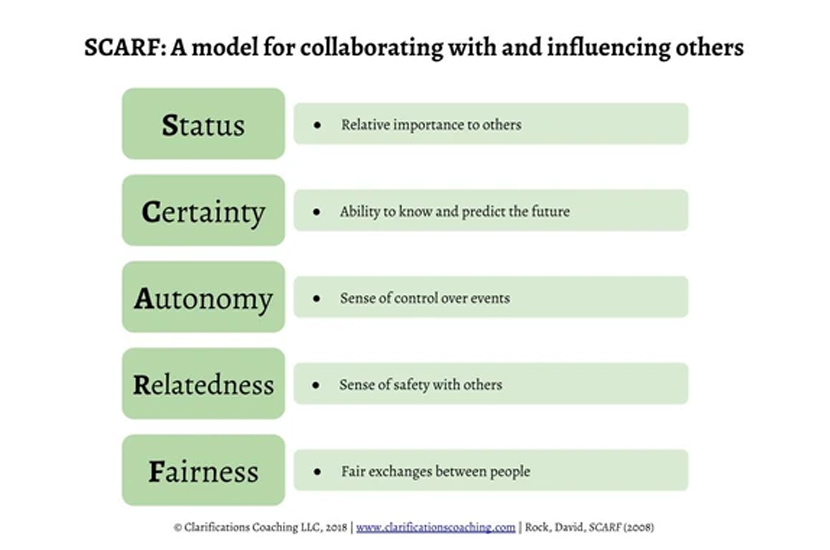

The SCARF model refers to five domains of human social experience:

These five domains activate either the “primary reward” or “primary threat” circuitry (and associated networks) of the brain. For example, a perceived threat to ones Status activates brain networks similar those activated by a threat to one’s life. In the same way, a perceived increase in Fairness activates the same reward circuitry as does receiving a monetary reward.

Labeling and understanding these drivers can help in two ways: First, knowing these drivers can cause a threat response enables people to intentionally design interactions to minimize threats. For example, knowing that a lack of Autonomy activates a genuine threat response, a leader or educator may consciously avoid micromanaging employees or students. Second, knowing how to use these drivers to activate a reward response enables leaders to motivate others more effectively by tapping into internal rewards thereby reducing the reliance on external rewards (such as money). For example, a manager might grant more Autonomy as a reward for good performance.

When an individual encounters a “reward”, it will likely lead to an approach response. When they encounter a “threat”, it will likely lead to an avoid response. The significance of this in a leadership context becomes apparent when one discovers the substantial effect these responses can have on perception and problem solving.

When a human being senses a threat and their body produces an avoid response, resources available for overall executive functions in the prefrontal cortex decrease. The result is literally less oxygen and glucose available for linear, conscious processing. Thus, someone in this state is less likely to be able to solve complex problems and more likely to make mistakes. They are also less likely to perceive the subtle signals required for insight or the “aha!” experience. They shrink from anything perceived as “dangerous” and err on the safe side, with small stressors likely perceived as larger than they actually are. Obviously, this response is not ideal for collaborating with and influencing others.

On the other hand, an approach response is closely linked with the idea of engagement. Engagement is a state of being willing to do difficult things, to take risks, to think deeply about issues, and develop new solutions. This state is associated with positive emotions like interest, happiness, joy, and desire (leading to increased dopamine levels). Studies show that people experiencing these positive emotions can perceive more options when trying to solve problems (Fredrickson 2001), solve more nonlinear problems that require insight (Jung-Beeman 2007), collaborate better, and perform better overall.

Workplace engagement, in particular, involves the degree to which people put discretionary effort and care into their jobs. Its neural bases can be measured by the average levels of activation in the brain’s reward and self-regulation circuitry when people are thinking about or participating in work. Similarly, disengagement can be measured by the average levels of activation of the brain’s threat circuitry. It can be inferred, then, that engaged employees are experiencing high levels of positive rewards in the SCARF domains and that disengaged employees are experiencing high levels of threats in the SCARF domains.

Overall, the SCARF model can improve people’s capacity to understand and ultimately modify their own and other people’s behavior in social situations, thus being more adaptive. The model is especially relevant for organizational leaders and managers, organizational learning and development professionals, facilitators, trainers, coaches, consultants, and teachers as well as social workers, community aid workers, or anyone looking to influence others.

If you are interested in learning more about how to use the model in a workplace context, I’ve written another blog post about using it when measuring levels of employee engagement. Or, if you’re interested in seeing where your or your associates’ preferences land within the SCARF domains, the NeuroLeadership Institute offers a great SCARF Assessment online.